Contextual focus point: Frank Auerbach’s portraiture:

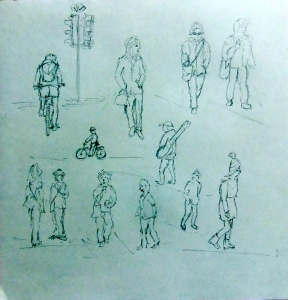

Frank Auerbach’s approach to portraiture is legendary and through it he makes some very interesting points about the nature of portraiture and of drawing. Research what makes Frank Auerbach’s portraits unique, and how he used the passage of time in them. Think about why he might have done that and make notes about how working from life differs from working from a photograph in terms of the way we experience the time spent. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/frank-auerbach-676

Research source material: frank auerbach

From Rembrandt, Sickert and Bomberg to Auerbach

Capturing the essence of a person visually is not an easy task. The self portraits below are all the artist’s attempt to convey, not just a flat image of themselves, but also, and more, a feeling and insight of sorts into how they perceive themselves to be, at a time, in time:

Rembrandt (1630) Self-portrait with beret, wide-eyed. [Etching]. Available at: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/my/collections/2329304–alie-rouw/rembrand-van-rijn/objecten#/RP-P-OB-697,1 [Accessed: 12 January 2019].

Sickert, W.R. (c.1896) Self portrait. [Oil on canvas] Leeds Art Gallery. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/self-portrait-37703/search/venue:leeds-art-gallery-leeds-museums-and-galleries-4864/sort_by/relationship.work_artist.name.keyword/order/asc/page/36 [Accessed: 12 January 2019].

Bomberg, D. (1932) Self-portrait. [Oil on canvas]. Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bomberg-self-portrait-t03265 [Accessed: 12 January 2019].

Auerbach, F. (1958) Self-portrait. [Charcoal and chalk on paper] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/frank-auerbach/auerbach-introduction [Accessed: 22 December 2018].

Auerbach, F. (2014) Self-portrait. [Graphite on paper] Available at: http://www.marlboroughlondon.com/artists/frank-auerbach-2/ [Accessed: 3 January 2018].

Auerbach developed a fascination, some might say an obsession, for inviting a small coterie of people to sit for his portraits, including: Estella (Stella) Olive West (“E.O.W.”); Julia Yardley Mills (“J.Y.M.”); Catherine Lampert and William Feaver.

“I find myself simply more engaged when I know the people. They get older and change; there is something touching about that, about recording something that’s getting on.” Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/frank-auerbach/auerbach-introduction [Accessed: 3 January 2019].

Auerbach, F. (1960) Head of E.O.W. I. [Oil on board] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/auerbach-head-of-e-o-w-i-t06682 [Accessed: 2 January 2019].

“Ridges and gullies, dragged paint, violent swirls across the surface. Busy in a world of restless squashy movement. Thick layers, scraped back, creating the image through working with the paint and the surface.”

(From: Phaidon Press (1994) The Art Book.,p.21.)

Hands, brushes, palette knives, putty scrapers and paint squeezed from the tube get applied to the task – hands on in spades with heavy impasto work – scraping back, layering and sculpting the essence of the person he sees before him.

The brush mark making in Head of J.Y.M. No.1 seems to combine an impasto application to a more fluid capturing of the sitter:

Auerbach, F. (1981) Head of J.Y.M. No.1. [Oil on canvas] Tate. Available at: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-artists/frank-auerbach.htm [Accessed: 3 January 2018].

Auerbach, F. (1984-85) Head of J.Y.M. II. [Oil on canvas] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/press/press-releases/frank-auerbach-tate-britain [Accessed: 2 January 2019].

Auerbach, F. (2003) Head of William Feaver. [Oil on board]. Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/frank-auerbach [Accessed: 3 January 2019].

Auerbach, F. (2017) Head of Catherine Lampert. [Oil on board] Marlborough Fine Art. Available at: http://www.artnet.com/artists/frank-auerbach/ [Accessed: 3 January 2019].

There is an exciting energy in these portraits that pushes the traditional concept of portraiture to a level beyond what inspired and influence him in the works of Rembrandt, Sickert and Bomberg. It is almost as if Auerbach took his sitters apart in his mind as he applied paint, scraped back and re-painted, all the time seeking further into what he saw as the essence of their being.

The fact that he used the same band of happy models over many years enabled him to delve deeper into his memories of them and the triggers of seeing them sitting before him anew each time.

As a final comment, I would suggest that in viewing Auerbach’s portraits, I concur with the statements he made to film in The Last Art Film on the three areas that, for him, make a work of art. His portraits are not “immobile”, they are “engaging” to the viewer; there is “expression” and “the feeling of an idea”; and there is “tense surface character” in the mark making. His portraits are indeed “ineluctable”.

Notes taken from The Last Art Film – Auerbach, J. (2012) The last Art Film. Directed by Jake Auerbach [DVD]. UK: Jake Auerbach Films. [Accessed: 14 January 2017].

Whether or not the same energy and insightfulness would have/could have been captured in working from a photograph of his sitters is debatable. While a photograph might bring up a memory of the person or scene and the point in time when it was taken, there us no escaping the fact that addressing the subject in real time, and over time, has the potential to capture much more of the artist’s own acts of looking, thinking, changing, reflecting and doing into what becomes the completed (maybe never finished) piece of art.

Stuart Brownlee – 512319

13 January 2019